Note: I wrote the essay below for Mennonite Central Committee, reflecting on my two years in Haiti and the influence of my grandmother (Oma), Lois Kreider, an extraordinary badass who passed away in late January. This version has a few more fun photos!

—

On my first visit to Ramon St. Hilaire’s workshop, in a narrow alley in downtown Port-au-Prince, Haiti, I remember it smelled of fragrant, fresh-cut wood. Sawdust sparkled in the tropical air. Outside, stacks of wood from the obeche tree cured in the sun, waiting to be shaped into elegant bowls. During this visit, St. Hilaire showed me a newly sanded platter. I took it and turned it over in my hands, feeling something familiar in the smoothness of its form.

I had held a nearly identical platter, mahogany with a time-worn patina, just before departing for my Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) service in Haiti in 2016. My Oma, Lois Kreider, had shown it to me, explaining that my Opa, Robert Kreider, had visited MCC’s first projects in Haiti in 1962 and had made a stop in Port-au-Prince to visit a cottage industry of woodworkers.

Impressed with the quality of their work, he packed a suitcase of the mahogany pieces to show both my Oma and Edna Ruth Byler. They were involved with a fledgling MCC project that became today’s independent fair-trade organization, Ten Thousand Villages, which sells crafts from all over the world.

Holding St. Hilaire’s platter in my hands, I thought of Oma, who traveled the world working with artisans. Through her work, Oma was a bridge between those artisans and customers in Canada and the U.S. Her legacy is thousands of connections, linking people and cultures through the exchange of handmade goods. This same desire to support these meaningful global connections motivated me to work with artisans in Haiti.

From Bluffton to around the world

Oma’s history with fair trade started when she saw a beautiful piece of Palestinian needlework Edna Ruth Byler had hung on her wash line in Akron, Pennsylvania, while Oma and Opa were living there in 1961. Oma offered to lend a hand ‒ and her entrepreneurial spirit – to Mrs. Byler’s project: The Overseas Needlepoint and Crafts Project (eventually SELFHELP Crafts and now Ten Thousand Villages).

When Oma and Opa moved back to Bluffton, Ohio, Oma organized annual SELFHELP Crafts pre-Christmas sales in the basement of First Mennonite Church.

After several years of successful annual sales, Oma and other volunteers began to dream of having a shop selling fair-trade goods year-round. Oma came home from a trip to Manitoba, where she had learned about the first MCC Thrift shop, and eagerly advocated for the new store to be a combination of SELFHELP Crafts and a thrift shop. Oma volunteered to manage the innovative new shop.

In 1974, the Bluffton Et Cetera Shop opened as the first store in the U.S. to sell secondhand clothing and housewares, generating revenue for MCC’s programs, and fair-trade crafts, providing a steady sales outlet for artisans.

That year, Oma and Opa took several months to travel around the world visiting MCC projects. Opa described the trip as taking them “from the border of Somalia to the Kalahari Desert of Botswana to a then-peaceful Kabul in Afghanistan to the slums of Calcutta to tropical villages in Java to the mine-infested paddies of Vietnam.”

In each place, Oma put her master’s degree in textiles and her eye for design and craftsmanship to use. She met with craftspeople, especially women, making connections that would blossom into long-term trading partnerships with what is now Ten Thousand Villages.

Walking in Oma’s footsteps

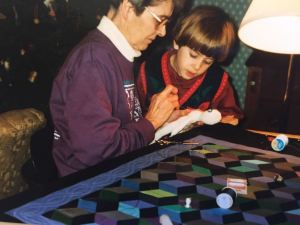

Holding St. Hilaire’s platter was not the first moment I realized that I was walking in Oma’s footsteps. As a child, I loved accompanying Oma and my mother to volunteer at Ten Thousand Villages. I learned about the lives and traditions of artisans as I wandered among Bangladeshi baskets and Indian necklaces.

I followed my passion for handmade traditions and fair trade all the way to Port-au-Prince, Haiti, to serve with MCC partner Comité Artisanal Haïtien (CAH; Haitian Artisan Committee). This Haitian fair-trade organization represents over 125 artisan workshops and has been a Ten Thousand Villages partner for decades.

Haiti has a rich creative tradition in which the island’s artisans make inventive use of materials, transforming cement bags into papier-mâché masks and discarded steel oil barrels into intricate metal art. St. Hilaire’s bowls and platters show ingenuity, too, because artisans have replaced the now-scarce mahogany with fast-growing obeche trees as a sustainable resource.

At CAH, I used my experience with Canadian and U.S. businesses and consumers to help artisans translate their creativity into designs marketable to a foreign audience. I played many roles: designer, curator, trainer, coach, storyteller.

As a curator, I selected pieces with unique appeal from artisans’ galleries, like Jonas Soulouque’s cut metal Tree of Life, which stood out for its intricately hammered, twisted trunk. As a designer, I imagined new ways to adapt specific skills, for example, inviting papier- mâché artists to create Christmas decorations like the dinosaur ornament. And as a trainer, I created workshops where I taught design ideas like seasonal color trends, helping artisans create new products in color schemes unfamiliar in Haiti’s bright tropical environment.

Over the course of my time with MCC in Haiti, I often imagined Oma interacting with craftspeople on her trips. As an accomplished craftswoman and curious traveler, Oma became a bridge, linking these artisan communities for the first time to customers in Canada and the U.S. through handmade objects that signified dignified income and a sense of global community.

Access to markets

In early January, I led an MCC Haiti learning tour to Cormier, a village a few hours south of Port-au-Prince renowned for its stone carving. There, we met master carver Heston Romulus, who leads a team of four artisans in creating innovative pieces like a leaf-shaped stone incense holder developed for Ten Thousand Villages.

This learning tour group, made up almost entirely of Ten Thousand Villages volunteers, gathered in a circle, admiring the stone pieces that the carvers exhibited on a table, as Heston talked about his creative process.

“Sometimes even from far away,” he told us, “I can see the piece that lies within the stone.”

Fair trade advocates like my Oma and Mrs. Byler understood that craftspeople around the world have no lack of talent. Instead, they suffer from unjust global systems: wealth inequality, lack of access to education and infrastructure and unbalanced trade policies. Fair trade recognizes the skill, creativity and resourcefulness of artisans and provides the missing link: access to a market.

For a craftsperson like Heston, access to a market like Ten Thousand Villages means months of income for him and his team—and even more if the orders continue. Given this, Heston was delighted to hear from our group that his leaf incense holders had been popular purchases during the holiday season.

Being a bridge

In the years between Oma’s travels and my service in Haiti, fair trade has grown and evolved. Locally run organizations like CAH coordinate their own production and logistics. Opa’s suitcase has been replaced by shipping containers.

In Ten Thousand Villages stores, paid staff now work alongside volunteers. Similarly, MCC’s approach to relief, development and peacebuilding evolved over time to focus on supporting visionary local partners, valuing community-rooted expertise and wisdom—a philosophy very similar to that of Ten Thousand Villages, which values the beauty of community craft traditions and dignity of craftspeople.

Yet through these changes, as Oma said in a 2014 speech honoring the Bluffton Et Cetera Shop’s 40th anniversary:

“There are some things we do not want to see changed: The commitment of so many dedicated persons. The consistent vision of shops to care about local and global communities. The satisfaction of working together with those of other churches. The meaningful program of MCC and the awareness it brings of needs and challenges from around the world.”

This is what I learned from Oma: that we each have an opportunity to be a bridge. Oma saw that a handmade platter is not just a beautiful, functional object but is also a source of dignity, a spark of global curiosity and a vessel for human connection.

We’d been walking in the midday sun for two hours when we stopped for a quick rest in a shaded area of clean-swept dirt that served as a community space. We each sucked down a sache dlo (plastic packet of fresh water) and watched an animated game of dominoes: four men playing at a table, with several heckling onlookers.

We’d been walking in the midday sun for two hours when we stopped for a quick rest in a shaded area of clean-swept dirt that served as a community space. We each sucked down a sache dlo (plastic packet of fresh water) and watched an animated game of dominoes: four men playing at a table, with several heckling onlookers.